Bleeding the Pressure

May 16, 2017

This is the fifth post in a series on the Jackson School-led mission to drill for samples of methane hydrate from under the Gulf of Mexico for scientific study. Read the fourth post here.

The science team on the Helix Q4000 took a break from pressure coring Monday to conduct some tests on the specialized coring tool and was greeted with some good news Tuesday morning: The tool deployed successfully during the test and retained pressure, bringing hope that the alterations made by Geotek engineers over the last 24 hours will improve the mission’s success rate.

Even as the coring came to a temporary halt, the researchers aboard were busy conducting science.

Among the tests the team is running on the pressurized core is quantitative degassing. This involves holding the core in a pressurized vessel and slowly bleeding off the methane hydrate and water into a bubbling chamber and carefully measuring as the pressure rebounds. This occurs because the frozen methane hydrate, which is under intense pressure, contains roughly 160 times the methane per volume as it would under surface pressure. As pressure is reduced, the methane dissociates, or melts, and the methane in the hydrate expands, causing pressure to spike again. By carefully conducting this test over a period of time, the scientists are able to obtain exact measurements of the amount of methane in the core sample.

“We need to know the amount of methane in the core because it gives us a good metric to quantify how much methane is in the area where we took the core from,” said Josh O’Connell, a Jackson School research science associate. “And then we can actually extrapolate that out further across the area.”

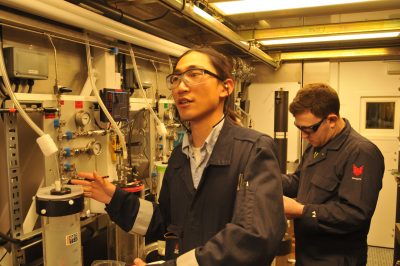

The degassing duties were shared throughout the team Monday night and into Tuesday morning, as members took turns bleeding off the gas and taking measurements every hour. The process of actually working with pressurized core was very exciting for Jackson School Ph.D. student Tiannong “Skyler” Dong, who was used to dealing with methane hydrate analysis on a much more theoretical basis.

“Usually we just drill a hole and put some sensors into the hole and take some geophysical measurements, and with those geophysical measurements we try to infer the concentration of methane hydrate, but we cannot verify the interpretation,” he said. “So by taking this (gas) out, we can actually know very precisely how much methane hydrate is in the sediment.”

The mission, explained lead scientist and Jackson School Professor Peter Flemings, offers a learning environment that no classroom can match.

Jackson School Research Associate Ethan Petrou emphatically agreed. Petrou took an energy exploration class from Flemings at The University of Texas at Austin during his year abroad from University College London and was thrilled to be invited back to Texas a year later to take a staff position on Flemings’ research mission.

“Doing science in the middle of where you do your daily research is actually amazing. You’re never on site. You’re never this close to the data. You’re never this involved,” he said. “It’s definitely helping me grow as a scientist. To actually see things I’ve read in text books. I’m developing new ideas and talking to people I never would have come in contact with. It’s definitely given me a lot of ideas to think about.”

Anton Caputo, Jackson School Communications Director